Exploring Ink Painting and Tradition in the Digital Era: Visual Experience in Recent Works by Su Huang-Sheng

by INK STUDIO Curator

Tina Liu

Tina Liu

Introduction

Mesmerizing colors, fine-line gongbi brushwork, discordant pictorial space yet cohesive, integrated composition, Su Huang-Sheng’s ink paintings present us with artistic experiences that engage deeply our formal expectations of traditional Chinese painting yet resonate naturally and instinctually with our visual experience of daily life in our contemporary, digital era. This makes his painting a dialog between two very different approaches to visuality—one tracing the history of ink painting and its traditional practice, the other exploring first-personal visual experience and its expression in contemporary visual culture. His painting process, as a result, becomes Su’s ongoing exploration of the fundamental meaning of painting itself—and the practice of ink painting more specifically—as reflected in his first-person perceptual and psychological experience of living in the world today.

Visual Experience: Accumulation, Connection and Transformation

Born in 1987 in Taoyuan, Taiwan, Su Huang-Sheng grew up in a digital era overloaded with information and visual images. The abundance and complexity of daily visual experience thus became an important part of the nature of his artistic language and practice. He draws materials from ordinary and trivial objects seen in the quotidian world—trees decorated with neon lights, plants with exotic colors and patterns, tree trunks with irregular textures, homeless people on the street, the small corner of his rooftop balcony—and turns them into pictorial scenes full of oddness and estrangement. Struck by the diversity and divergence of visual sources and formalistic means employed by Su, people often wonder how he manages to achieve such coherent end results. Su describes it as a long and complicated process—from the moment his eyes receive visual information to the execution of the final painting—a process that requires an iterative accumulation, connection and transformation of his visual materials.[1]

It is not uncommon for people of Su Huang-Sheng’s generation to document their visual experience through digital devices like the camera or smart phone, in the format of photos or short videos. Yet, accumulation here not only refers to the gathering and documentation of what we see but more importantly the accumulation of seeing over time as our brain neurologically processes and digests these visual experiences. But for Su, this process also allows him to make cross-context connections between different embodied experiences. And it is usually these connections that interest and inspire him the most.

While looking at a black marble tile floor spotted with the white reflections of overhead spotlights, Su suddenly thinks of a dark starry night, a subject that has always fascinated him and that he loves depicting. Both experiences take part in his handscroll Journey to the West (2020), which begins from the left with a mysterious starry night then seamlessly transitions into the spotted tiled floor, naturally leading the viewer from the open outdoor skies to an enclosed, indoor setting (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Journey to the West (detail)

When he was in New York for an artist residency program, Su became curious about the plumes of steam coming through the manhole covers on the street. It evoked in him visual memories of the familiar environment around his studio in Beitou—a district to the north of downtown Taipei famous for its rich geothermal resources. In his Hot Valley in Beitou (2019), hot steam rising from the ground becomes a repeated theme throughout the central vista of the composition. Executed in his fine gongbi or “meticulous” brushwork using the baimiao or “outline” technique, Su’s rising steam resembles the auspicious clouds seen in traditional gongbi paintings (Fig. 2). This visual motif, however, starts out as neither steam nor clouds but as smoke rising from the lit cigarette of Su’s young male protagonist shrouded in the dense woods to the right of the central scene. Three completely different natural phenomena—cigarette smoke, geothermal steam and floating clouds—Su connects through a shared formal depiction, thereby creating a pictorial motif that not only unifies the different spatial perspectives structuring the composition but also links personal action (smoking a cigarette), natural phenomena (geothermal heat), and cultural metaphor (auspicious clouds) into a chain of interconnected themes.

Fig. 2 Hot Valley in Beitou (detail)

It is difficult to tell whether Su Huang-Sheng is fully conscious of the complex process entailed in transforming daily visual experience and its memory into a final painting as he himself testifies that the actual painting process is also a process of self-exploration and self-realization. Sometimes, he freely admits, the cross-context connection between certain visual experiences he only discovers after he has finished the entire process and reflects retrospectively on the overall result.[2]Nevertheless, it is exactly this process of accumulation, connection and transformation that allows Su and his explorations of ink painting practice to be in constant dialog with his personal life and with contemporary society.

Illusionistic Materiality: The Painted Surface and the Glowing Screen

Like many contemporary ink artists, Su Huang-Sheng pays serious attention to his choice of painting materials, especially the material surface—paper, silk or metal foil. For him, the selection itself is an important part of the entire painting process. The characteristic materiality of each medium contributes to the final visual effect of the finished painting, creating a tension between the material surface and the painted surface.

The paper Su chose for two of his latest figure paintings, Boxing IIand Venus II, has a relatively rough texture and contains thick fibers that are visible throughout the painting surface. His dry brushwork and soft gradation of colors perfectly accommodates the material quality of the paper. The short, irregular lines that define the muscular body of the boxer and the pleats on the girl’s shirt echo the natural shapes of the fiber in the paper (Fig. 3), initiating an intertextual dialog between the material surface and the painted surface. This requires the artist to plan for the experiential qualities of his materials when approaching his overall composition, his application of ink wash as well as his brushwork.[3]This requires the viewer, similarly, to constantly process two different kinds of visual information, one material and one illusionistic, attending to the experience of each distinct surface while unifying them into a coherent perceptual whole.

Fig. 3 Venus II (detail) & Boxing II (detail)

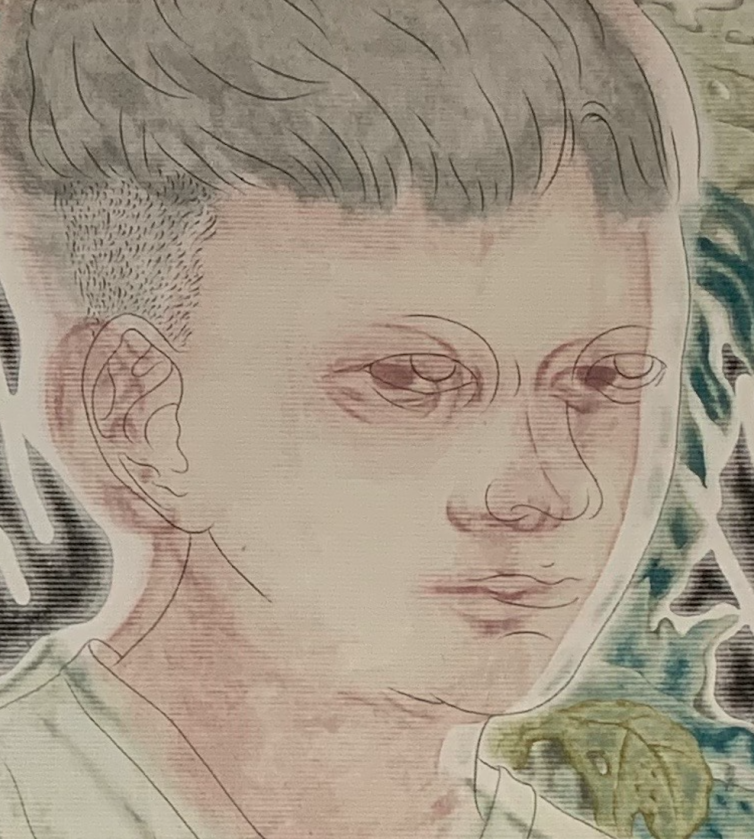

What makes this challenging experience even more intriguing is yet another kind of illusionistic surface. People who are familiar with Su’s works might already noticed one strange visual effect in his figure paintings. As seen in Young Man (2020), the above mentioned Boxing II and Venus II, as well as an earlier work Landscape 11 done in 2017, Su depicts his figures against a dark background and usually with pale skin tone executed in extremely light washes or nearly-untouched expanses of paper. Without a sharp-edged contour, Su instead defines the shape of his figures by a soft gradation of light and dark colors, which produces a “glowing” visual effect, as if his subjects were illuminated from within or, alternatively, viewed on the backlit screen of a computer or smart phone (Fig. 4). This challenges both our own visual experience and our perception of traditional ink painting. Both the material surface and the painted surface now give way to a third illusionistic surface of a digital screen, on which the figures seem to be displayed, or to a fourth mental space in which metaphysical subjects illuminate themselves.

Fig. 4 Young Man

This glowing screen effect is also reinforced by certain qualities of the material surface. In Young Man, for example, Su uses a Song-style mulberry paper with striped patterns. Some viewers may find the stripes somewhat distracting, interrupting the coherence of the visual illusion. Yet, Su chose this specific type of paper exactly because of the striped visual effect revealed in the final painting, which reminded him of the vertical lines that often appear in old movies resulted from scratches on the film surface, or of the horizontal scanlines that appear on old television screens when the signal is unstable.[4] Both are glowing screens on which stripes interrupt the displayed images, a visual experience stored in Su’s childhood memory and then re-interpreted in his ink painting. Su’s use of metal foil is also related to this glowing effect, as for him, its highly reflective surface displays optical qualities which cannot be found in any other traditional Chinese painting medium.[5] In this sense, the metal foil itself becomes a screen on which the painting is executed (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5 Landscape in the Apartment IV

Su has even considered mounting ink painting as a light box.[6] Though just a rough idea with unknown results and pending further experimentation, the light box installation will add a physical rather than illusionistic glowing effect to the painting, which makes the final visual effect even more complex and intriguing. Through all of the above-mentioned methods of exploration, Su Huang-Sheng keeps challenging and expanding the potentiality of traditional painting materials, providing them with new possibilities and new meanings.

Traditional Ink Painting Practice: Legacy and Innovation

Su Huang-Sheng established a solid foundation in painting techniques—particularly meticulous gongbi styled painting with mineral pigments on a range of material grounds—as well as a comprehensive understanding of the history of Chinese painting during his master’s level studies at Taipei National University of Arts. This professional and systematic training as well as his ongoing explorations as an independent artist after graduation have enabled Su to develop a distinctive artistic practice that is deeply grounded in the traditional ink painting language and yet reflective and responsive to his personal, first-person perceptual experience living in our highly-mediated digital era.

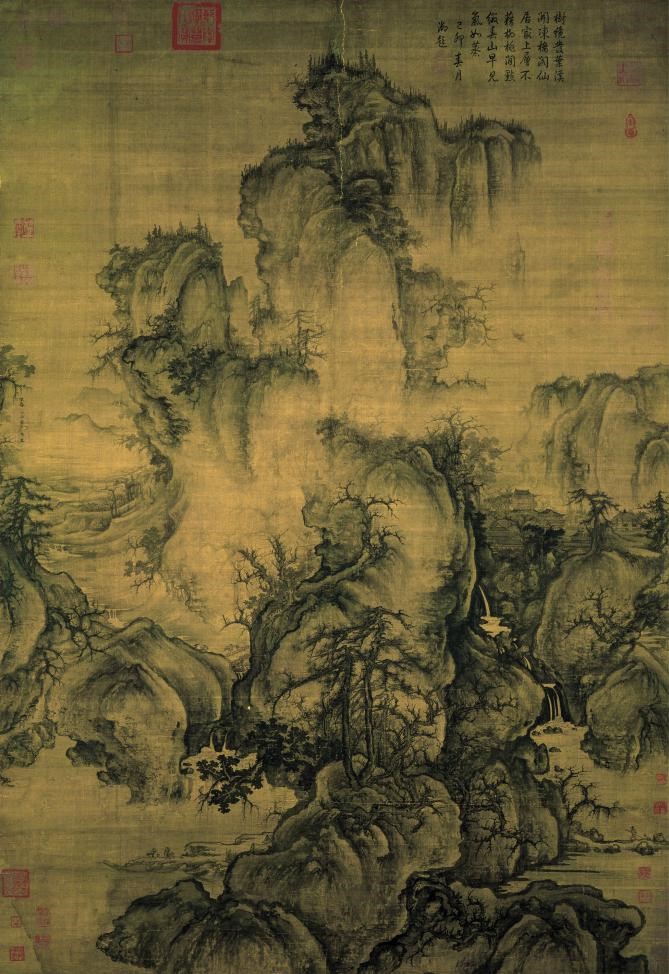

One illustration of Su’s unique approach to traditional and contemporary visuality is his adoption of the moving perspective and the shifting treatment of pictorial space in the handscroll format or a horizontal composition. Unlike the linear perspective that prevailed in Western painting during the Renaissance—which employs a single, fixed viewing point in order to achieve an illusionistic space—the moving perspective adopted in Chinese landscape painting allows and invites the viewer’s eye to navigate freely throughout the composition, as the fundamental aim of a Chinese landscape painter is to record “not a single visual confrontation but an accumulation of experience touched off perhaps by one moment’s exaltation before the beauty of nature”[7] (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6 Guo Xi, Early Spring, hanging scroll, ink and color on silk, 158.3 x 108.1cm. National Palace Museum, Taipei.

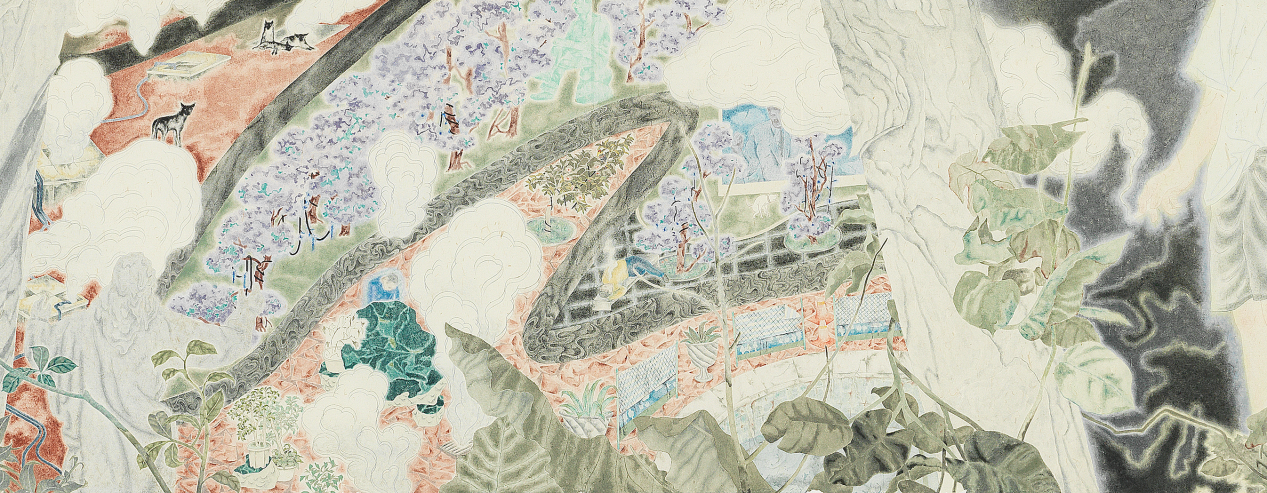

How, then, was this moving perspective achieved in Chinese landscape painting? The “Three Distances” principle summarized by the preeminent landscape painter of the Northern Song dynasty Guo Xi (c. 1020 – c. 1090) in his treatise The Lofty Message of Forest and Streams (Linquan Gaozhi) provided three different approaches to landscape composition that demonstrate a moving perspective: “high distance” (gao yuan), “deep distance” (shen yuan), and “level distance” (ping yuan).[8] In Su Huang-Sheng’s long handscrolls or horizontal works, he often combines different approaches together, enabling the shifting of time and space, viewing point as well as perspective. In the last section to the left in Journey to the West (Fig. 7), for instance, he employs the “deep distance” method in the depiction of the garden scene, with trees, rocks and the little bridge in layered arrangement, leading us to the space at the back where a man is operating a machine behind the rocks; as well as in his depiction of the dense foliage to the left, where different kinds of leaves overlap one another in rendering a close-in space. The water in the middle, in contrast, is depicted using the “level distance” approach in which the eye’s movement over the flat, horizontal surface of the river conveys spatial depth and recession. Su’s adoption of the “Three Distances” principle is also seen in the horizontal work Landscape 11, where the water around the bathing figure is depicted using the “level distance” method while the forest jungle to the right and the thick foliage to the left are depicted using the “deep distance” method.

Fig. 7 Journey to the West (detail)

For a viewer who has a basic understanding of traditional landscape painting, the above treatment of space and perspective will be familiar. What is visually fresh and challenging, however, is the drastic change of time and space achieved through manipulating the viewing distance, so dramatically that a coherent composition contradicts sharply the distorted pictorial space. In his Hot Valley in Beitou, Su divides the painting into three sections through the placement of three stout trunks in the viewer’s immediate foreground. The first section to the right shows an enclosed and intimate space where a headless young boy is smoking. The size of the figure and its surroundings suggests a close-up viewing distance, as if the viewer is standing right in front of the boy between the first two trees. Moving our eyes then to the next section in the middle by following the smoke rising from his cigarette, we suddenly realize that the smoke has become a cloud and find ourselves high up in the sky looking down at an exquisite garden unfolding along a meandering stream. The size of the figures, trees and plants are all reduced as we zoom out and view the scene from afar and from above. Following the stream’s path, we encounter a figure in yellow lounging on a bench while smoking, a raptor perched in the high branches of a tree, a second figure in blue, head hung perhaps in melancholic daydream, and a statue seen from above and behind of a robed, long-haired figure (perhaps Christ), arms opened in an embracing gesture of compassion. Magically, the meandering stream turns into a winding path as the viewer continues through the fantastical garden until he or she exits from the upper left corner where the path, partially hidden behind the third foreground tree trunk, transforms, yet again, into an abstract black line resembling an electric wire (as seen from up close) not unlike the black lines intertwined in the garden trees (as seen from a distance). Zooming in again from a foreground perch, the viewer now finds him or herself looking from above at the corner of a rooftop balcony, probably from the window or balcony of a nearby building. Such dramatic change of pictorial space provides the viewer with a nearly theatrical visual experience, as if one were seeing the whole composition through the shifting, high-powered zoom-lens of a camera. Among other things, this offers us new perceptual frameworks for interpreting the moving perspective of the traditional Chinese landscape that feel not archaic or formalistic but instinctual and immediate in a world we experience both directly and mediated whether through movies, television programs, or even on our own cell phones whenever taking a photo.

Su’s innovative approach to the ink tradition based on his personal visual experience is also seen in his unique treatment of traditional gongbitechnique and painting process. In Young Man and Landscape 17, Su demonstrates his mastery of the traditional gongbi technique in producing a realistic and convincing visual image, which starts with ink outline rendered with delicate and accurate brushwork and is then followed by graded color-wash infill. What is unusual or visually confusing is that he deliberately offsets the contour from the coloration, resulting in a disassociated double image (Fig. 8). This requires a higher level of technical dexterity and extra concentration during the painting process as he is constantly fighting against his painterly instinct to align color with outline. The inspiration for such spatial separation of the two came from his visual confrontation with a mis-aligned woodblock print discarded by students from the prints department at his university. A product of an accident or mistake during the printing process,[9] the misaligned print became visual provocation for Su, whose artistic response was to question the outline-and-color-fill gongbi painting process he had been practicing for years and often taken for granted. Similarly, the disassociated images that Su subsequently produced, by decoupling the viewer’s perception of outline and coloration thereby frustrating any resolution into visual illusion, exposes to the viewer’s gaze the hidden methods of the gongbi painter.

Fig. 8 Landscape 17 (detail)

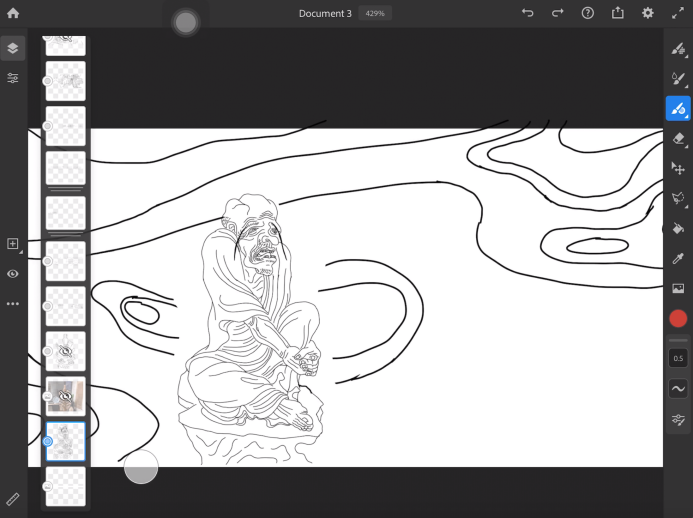

Another traditional gongbi painting process that Su follows and to which he adds his own creative component is the use of a preparatory drawing or tracing copy. Gongbi painting as it was originally practiced in the Song Dynasty pursued a realistic and accurate visual representation of its subject, however, the ink medium did not allow adjustment or overpainting as in oil painting. As a result, gongbipainters of the Song dynasty would usually outline the basic composition and contours of the subject being depicted in a detailed preparatory drawing which, after multiple rounds of revision, would be placed backlit underneath the final paper or silk to serve as a tracing copy for the finished work. Su employed the same procedure and used to execute his preparatory drawings using a pencil on paper until the launch of Apple Pencil in 2015, which has enabled him, instead, to draw on his iPad using drawing software. This opens up new possibilities for Su, allowing him to revise, compare and try out different visual solutions back and forth, multiple times until the most satisfying result is achieved. When he feels stuck in the middle of his painting process, he takes a photo of the unfinished work and tries different solutions and directions using the software on the iPad—changing compositions, erasing unwanted parts or replacing certain images—without touching the actual painting (Fig. 9). Gradually, he discovered that the visual result on the iPad was also something he wanted to capture. Thus, he started to selectively integrate visual effects—such as the digital lines produced with a stylus on an iPad—using his gongbibrush. This explains the visually awkward, wire-like lines that occur in many of his compositions, The Pond, for example, as well as the lines in the Chaos series executed on metal foil. Though the final visual effect of his painting seems a complete departure from that of traditional ink painting, Su realized that his practice is directly analogous to what the gongbi painters have always done: that is, use a set of established artistic practices in order to reconcile first-hand perceptional experience with experience as mediated by works of art. Viewing a natural landscape in relation to paintings of landscape for artists in the past is, for Su, not unlike him experiencing life through his own senses and then seeing it mediated through a digital image on an iPad.[10] This homology of visual experience is what connects Su’s contemporary visuality with ink painting practice of the past.

Fig. 9 Journey to the West(detail). Comparison of two digital drawings on iPad and the final painting.

Perhaps it is inevitable that every contemporary ink artist has to face the challenge of how to deal with the relationship between tradition and contemporaneity. What Su Huang-Sheng has shown us in his paintings is a distinctive approach to this common challenge that synthesizes his first-person visual experience, his exploration of the materiality of traditional ink media, and an approach to traditional gongbi painting techniques and practices that is both innovative and thoughtful. Instead of being stuck in a rigid dichotomy between past and present, Su has found a channel that allows him to be in ongoing dialog with both the history of ink painting and with our lived, contemporary experience, producing a formal visual representation that is both instinctually immediate and deeply historically resonant. This new direction and perspective opens up new possibilities for contemporary ink painting—possibilities for a new generation of young artists like Su Huang-Sheng to explore.

[1]Interview with Su Huang-Sheng by Tina Liu, June 8, 2020.

[2] Ibid.

[3]The fiber in the paper is actually invisible during the painting process and can only become visible after the mounting. [4] Interview with Su Huang-Sheng by Tina Liu, July 6, 2020.

[5]Interview with Su Huang-Sheng by Tina Liu, June 8, 2020.

[6]Interview with Su Huang-Sheng by Tina Liu, July 6, 2020.

[7]Michael Sullivan, The Arts of China, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984, p. 156,.

[8] “High distance” refers to the perspective of altitude, depicting a towering landscape as if the viewer is looking up ahead from below at the foot of the mountain. “Deep distance” refers to the perspective for representing depth, which is often revealed by depicting the folder layers of a landscape, giving a feeling of mountains beyond mountains. “Level distance” refers to the perspective of panorama, assuming that the viewer is looking out across a landscape from a comparatively higher vantage point with an aerial view that is able to capture the broad and wide stretch of a scene that spreads flatly from the viewer’s location and extends off into the distance.

[9] In traditional Chinese woodblock print, the Song gongbi technique is reproduced using multiple printing blocks: one carved woodblock impresses the ink outline of the painted forms and subsequent woodblocks impress the color fill. Proper alignment of the multiple woodblock impressions is necessary to achieve a coherent, illusionistic result. Alignment errors, however, are not uncommon.

[10]Interview with Su Huang-Sheng by Tina Liu, June 8, 2020.